Inside the food baskets of Bangladesh

From the sun-baked paddy fields of the northwest to the

mango orchards of Rajshahi and the vegetable fields of Rangpur, the country's

agricultural heartlands are evolving. Once dominated by rice, these "food

baskets" are now producing a growing mix of grains, fruits and vegetables

-- defining the country's rural economy and the plates of millions.

Is there any part of Bangladesh untouched by agriculture?

Perhaps not, unless one counts the concrete expanses of cities like Dhaka. Even

that is debatable. In the capital, as in other towns, rooftop gardens brim with

fruit trees, tomato vines and brinjal plants.

Across the countryside, cultivation is not a pastime but a

way of life. Certain districts have become major suppliers for the rest of the

country, producing rice, maize, wheat, potatoes and vegetables in volumes large

enough to feed cities, including Dhaka, home to nearly 2 crore people.

Today, anyone visiting the western and northwestern

districts can see the changes in cropping patterns. Large paddy fields still

dominate, but they now share space with vegetables, fruit orchards, and maize.

This shift is part of a gradual diversification. Fields that once grew a single

crop for most of the year now produce two or three.

Cropping intensity, or the number of crops grown on the

same land in a year, has risen from 171 percent in the early 1980s to about 200

percent today.

In Meherpur, a district on the western border, the figure

is 278 percent, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). In

neighbouring Chuadanga, it is 265 percent.

"Once we had two crops a year. Now we grow three. Some

farmers grow two rice crops and maize, while some grow rice and

vegetables," said Wasim Royel, a farmer from industrial township Darshana

of Chuadanga.

The major change took place in the last 15 years.

"Availability of hybrid seeds has been the major driver for increasing

cultivation. Now, no one keeps their land fallow."

According to Royel, rice can be harvested in 90 days on

average now, leaving time for maize, which takes 130 days, and vegetables.

"In Meherpur, you will see that vegetables are grown throughout the

year."

Irrigation has been another key factor.

"The breakthrough in farming in our area came after

the introduction of irrigation and affordable shallow tube well pumps,"

said Samadul Islam, a 50-year-old farmer of Meherpur district.

"In my childhood, only one crop was grown in a vast

area. Now we can safely cultivate three crops a year," he said. The

district's higher land also helps, with less waterlogging and earlier planting.

Bangladesh has about 45.93 lakh acres of triple-cropped

land out of 3.93 crore acres of gross cropped area, the total sown once or more

in a year. Some regions now specialise in particular crops, shaped by climate,

soil and infrastructure.

RICE

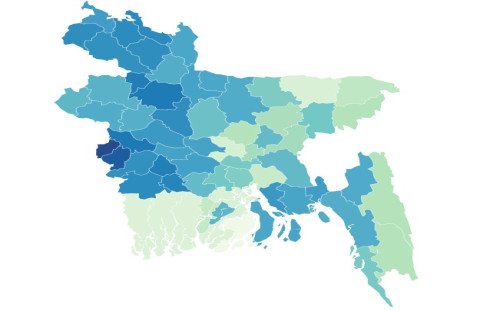

Five northern districts -- Mymensingh, Sunamganj,

Naogaon, Dinajpur and Bogura -- produce nearly a fifth of the national

rice harvest across Aus, Aman and Boro seasons, said Mohammad Khalequzzaman,

director general of the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI).

Mymensingh district is the largest Boro producer,

contributing 5 percent of total output, followed by Sunamganj, Naogaon,

Netrokona, Bogura, Jashore and Dinajpur. Sunamganj accounts for 4.5 percent of

total Boro rice, the main dry-season crop, which yielded an estimated 2.10

crore tonnes in the fiscal year 2023-24.

"Historically strong in Aman rice, Dinajpur is now

expanding into Boro. The northwest bordering district alone contributes 5

percent of total rainfed Aman rice," said Khalequzzaman.

"These areas have become major rice producers due to

favourable soil, stable weather patterns and relatively low risk of natural

disasters like droughts and floods," said the BRRI DG.

MAIZE

Maize, barely grown a generation ago, is now Bangladesh's

second-largest grain, with about 46 lakh tonnes produced annually. Chuadanga

accounts for over a tenth of the total. Dinajpur leads in volume, and Rangpur

division produces more than half the national harvest.

"Farmers are increasingly opting for crops with better

returns, signalling a shift in these historically rice-dominant regions,"

said Khalequzzaman.

In parts of Dinajpur, maize has replaced paddy in response

to rising demand from poultry and aquaculture feed industries.

"Maize production is also concentrated in Manikganj,

Rajshahi, Jamalpur and Natore. Twelve areas, including Chuadanga district and

the Rangpur division, account for around 80 percent of total maize

output," said Muhammad Rezaul Kabir, senior scientific officer at the

Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute.

WHEAT

Wheat is mainly grown in Thakurgaon, Chapainawabganj,

Natore, Rajshahi, Pabna, Faridpur, Naogaon, Panchagarh, Meherpur, Kushtia,

Rajbari, Bhola, Kurigram and Dinajpur.

These districts produce about 90 percent of the crop.

"These areas benefit from cooler, drier winters,

fertile loamy soil, reliable irrigation and a long tradition of cereal

farming," Kabir said.

FRUITS

Fruit production is shifting north and to the Chittagong

Hill Tracts, said Md Mosiur Rahman, principal scientific officer at the

Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute's fruit division.

"Rajshahi, Natore, Naogaon and Chapainawabganj excel

in mangoes, lychees, guavas, bananas and papayas. The Hill Tracts, once

dominated by jhum, are seeing systematic orchards of jackfruit, bananas,

pineapples and even mangoes," he said.

In Rajshahi and Naogaon, groundwater levels and soil suit

fruit production, especially mangoes. In the hills, higher ground reduces

root-level waterlogging. Land once marginal is now being used commercially,

with large-scale orchards replacing homestead cultivation in parts of Natore

and the Hill Tracts, he added.

Higher profitability and access to hybrid seeds, many from

India, have spurred mango cultivation in Naogaon, said BRRI DG Khalequzzaman.

Newer fruits are also gaining ground. Dragon fruit is now

among the top six in national output. Guava, once a minor crop, is widely grown

and helps reduce reliance on imported apples.

According to official data, the top five fruits by volume

are banana, jackfruit, mango, guava and papaya. Bananas remain the leader,

though seasonality is a challenge.

"Most fruits are produced between April and August,

which limits year-round supply," Rahman said. "The processing

industry needs crops like bananas, lemons, guavas and certain mango or

jackfruit varieties that can be grown all year.

NORTH: THE NATION'S FOOD BASKET

Md Akhtar Hossain Khan, chief seed technologist at the

Ministry of Agriculture, calls the north the nation's food basket.

"Vegetables, fruits and high-value crops dominate

there, alongside substantial rice and wheat cultivation," he said.

Rangpur district is the largest potato producer, followed

by Dinajpur, Bogura and Joypurhat. Together, the northern districts grow

three-fourth of the country's 1.15 crore tonnes of potatoes each year.

Barishal leads in pulses, while Noakhali is emerging in

soybean. "We are seeing a shift from homestead farming to commercial-scale

production," Khan said.

Mahbub Anam, managing director of Lal Teer Seeds Ltd, said

rice is the backbone of the food basket, followed by potatoes.

He said, "Vegetables form a crucial part of the diet,

and production has surged over three decades due to hybrid varieties and better

seeds."

In the late 1990s, hubs such as Cumilla, the outskirts of

Dhaka, Bogura, Gaibandha and Jashore supplied about half the national vegetable

market. Production has since spread to Rangpur, Munshiganj, Narsingdi,

Barishal, Sylhet, Bhola, Chattogram and Manikganj.

"These 13 districts now produce about 75 percent of

vegetables," Anam said.

Some crops have found new strongholds. "Godagari in

Rajshahi has seen a boom in tomatoes. Onion cultivation has expanded to Pabna

and Manikganj. Papaya and taro have moved from household gardens to commercial

plots. Watermelon, once confined to Kaptai, is now grown from Panchagarh to

coastal Patuakhali and even Sylhet," he added.

Flat beans, once a Pabna speciality, are now grown in

Sylhet. Crop rotation, he noted, is becoming essential to protect soil health.

'DON'T SEE AGRI OFFICIALS'

Yet the abundance of production brings its own concerns.

Farmers like Royel and Islam acknowledge that increased cultivation has raised

incomes and improved living standards, but prices are volatile.

"When we get better prices, our hard work pays

off," Royel said. "But when prices fall, we lose interest. There is

no guarantee we will get a fair price."

A lot depends on the mercy of the weather, too.

Heavy rains this season damaged Royel's fields and Islam's

banana orchard. Both say they rarely see agricultural extension officers.

"We don't see them in our fields," Royel said.

"Farmers would be encouraged if they visited and advised us on new

technology."

Islam raised another issue. "Pesticides are weak. We

have to spray twice a day on crops like brinjal. We are being cheated."

"The government should know that if we cannot produce

food, national food security is at risk," he said.